Gaia: the galactic mapmaker that is leading a ‘silent revolution’

University of Leicester space scientists are marking the anniversary of a space telescope that aims to create the most accurate and detailed 3D map of our galaxy.

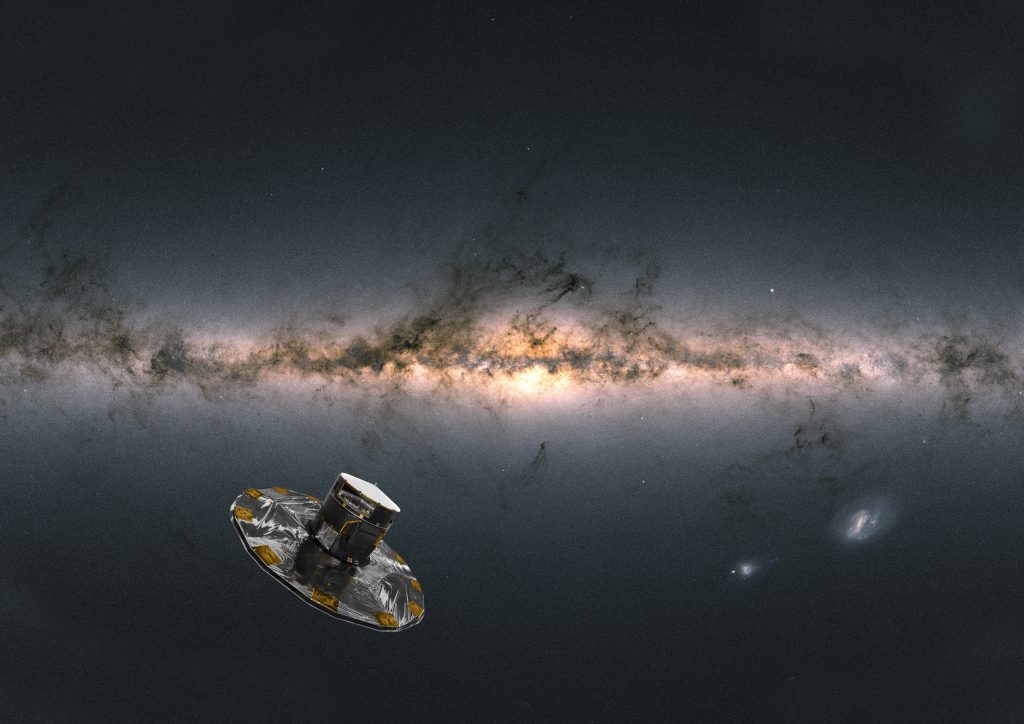

The European Space Agency’s Gaia mission has been observing and cataloguing billions of stars over the past ten years, mapping their motions, luminosity, temperature and composition. Launched on 19 December 2013, this massive survey is allowing scientists to answer fundamental questions about our place in the Universe.

Researchers from the University of Leicester have been at the forefront of the Gaia Collaboration since its very earliest days.

The Gaia space observatory orbits the so-called Lagrange 2 (L2) point, approximately 1.5 million kilometres away from the Earth. At this point the gravitational forces between the Earth and Sun are balanced, meaning the spacecraft can operate in a stable position with long-term views of the sky unobstructed by either body.

Gaia continuously scans the sky, measuring any change in the positions of stars and other objects over time resulting from the Earth’s movement around the Sun. Using the parallax method, scientists can then use any tiny shift in the apparent position of a star to calculate its distance from our solar system.

By repeatedly observing a billion stars, with its billion-pixel video camera, the Gaia mission is helping astronomers to determine the origin and evolution of our galaxy whilst also testing gravity, mapping our inner solar system, and uncovering tens of thousands of previously unseen objects, including asteroids in our solar system, planets around nearby stars, and supernovae in other galaxies.

The University of Leicester team is led by Professor Martin Barstow and has included Drs Claudio Pagani, Steve Sembay, Andy Read, Duncan Fyfe and Patricio Ortiz. They have a critical role in the mission – they are responsible for understanding and compensating for radiation damage that affects the on-board sensors. If this isn’t done, all the critical science from the mission would be degraded.

They have also played an important role in the scientific publications that accompany the Gaia data releases, bringing their wider research expertise to illustrate how Gaia data can be used. Leicester led work on the study of binary star systems revealed by Gaia and created a catalogue of 100,000 white dwarf stars that has been released to the community. They have also used machine learning techniques to classify the white dwarfs and determine their temperature and masses, providing a valuable resource for the field.

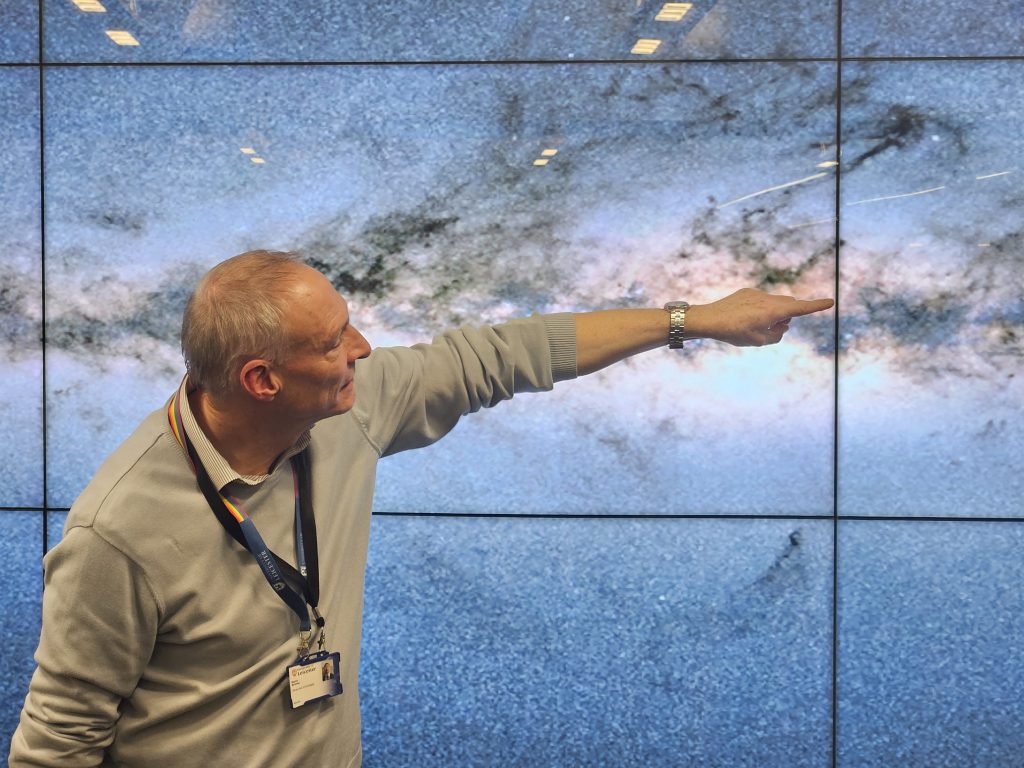

To mark the milestone, Professor Barstow hosted a talk on 14 December at Space Park Leicester that provided a fascinating journey through the achievements and insights gained from the Gaia mission.

Professor Barstow said: “The Gaia data constitute a silent revolution in our understanding of the Universe as they will underpin everything we know about planets, stars and galaxies. The work we have contributed to the Gaia mission also finds application in new space missions which use sensors similar to those used by Gaia. We understand the behaviour of these in space which helps data processing in missions that will be launched soon such as SMILE.

“While Gaia will stop collecting data around 2025, the processing will need to continue, with Leicester support, for several years after that. A data release is planned for 2025, with the final release of the full mission data set expected in 2029.

“Gaia’s lifetime is limited by the gas supply in its propulsion system. This is used to keep Gaia stable and in its orbit. However, this gas is expected to run out sometime in 2025. Then Gaia will drift away from its location and will no longer be the stable platform needed for the observations. At the point the active data collection part of the mission will come to an end. However, it will have lasted twice as long as the originally planned 5 years.”